Different forms of carbon, such as processed natural graphite, pyrolytic graphite, diamond-like carbon, and synthetic diamond, offer lots of possibilities for maximizing conductive heat transfer.Synthetic diamond has already found its place as a common solution for heat spreaders inside semiconductor laser components, where temperature stabilization is of utmost importance for the laser wavelength stability. Also, larger heat sinks and heat spreaders made of natural graphite, pyrolytic graphite, or graphite-metal composites are already commercially available. Here graphite is replacing copper and aluminum, offering similar thermal properties to copper combined with a weight less than that of aluminum.

In daily use, however, the definitions of the above-mentioned carbon materials tend to be easily mixed. Discussions of the properties of these materials will comprise the subject matter of this and several upcoming Technical Data columns.

Note: a technical brief, published in ElectronicsCooling, August 2001, has already addressed the properties of natural graphite [1].

|

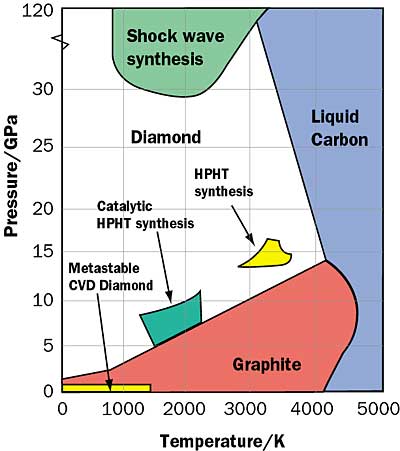

Figure 1. Phase diagram for graphite and diamond (source [2]).The differentiating factor between diamond and graphite is the crystal structure. For graphite, this consists of planar layers of hexagonally arranged carbon atoms. Inside the layers, the chemical bonds are very strong, but between the different layers the bonds are weak. This gives graphite its strongly anisotropic thermal, mechanical, and electrical properties. Diamond crystal, consisting of cubically formed carbon atoms, is isotropic.

The phase diagram shows the temperature and pressure conditions under which these different crystal structures are formed. The activation energy needed to change the lattice structure from one to another is high, causing us to have both kinds of crystals in our normal living conditions.

The first synthetic diamonds were manufactured by the High Pressure High Temperature (HPHT) process, where graphite was mechanically pressed at high temperature to create the conditions needed for forming the diamond structure, as shown in the phase diagram. The pressing could be done either with or without the addition of a metallic catalyst; pressing without the catalyst requires even higher pressure and temperature.The HPHT process normally creates crystals that have many defects, but these diamonds are nevertheless very useful for mechanical tooling purposes.

During the last 15 years it has been possible to produce perfect diamond lattices by using the Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) technique. Here hydrocarbon gases (such as CH4) are activated over a solid surface in an atmosphere having an excess of hydrogen. Activation can be accomplished by a hot filament or by electrical means using DC, RF, or microwave frequencies. The temperature of the substrate is typically 1000 – 1400 K.

Again the crystal lattice defined in the resulting material is that of a diamond with the true crystal structure, or diamond-like carbon, being mostly amorphous but including a microcrystalline phase. This type of mixed structure deteriorates the thermal conductivity, but also decreases the brittleness.

The room temperature thermal conductivity of diamond-like carbon is typically up to 1700 W/m K. For CVD diamond, values up to 2100 W/m K can be obtained. The maximum value depends largely on the “perfectness” of the lattice structure and on the presence of any impurities. The CVD diamond CTE at room temperature is in the range of 1×10-6 K-1 to 2×10-6 K-1, almost matching to that of invar.

Reference

- Norley. J., The Role of Natural Graphite in Electronics Cooling, Electronics Cooling, Vol. 7, August, 2001, pp. 50-51

- https://electronics-cooling.com/wp-content/uploads/2002/02/cphased.gif