I was doing my Sunday morning (2 a.m.) radio call-in show about electronics cooling (Hot Air on the Air with Tony K), when I heard a familiar voice on the line.

“Herbie in Hereford,” I greeted the caller, “You’re on the air with Hot Air.”

“First time caller, long time listener . . .,” the caller said.

“Wow. There must be an insomnia epidemic,” I interrupted. Johnny, the chain-smoking producer behind the glass, rolled his eyes at my attempt at humor.

Herbie said, “Insomnia? Who can sleep when you’ve got electronic thermal problems? Plus, I couldn’t get through to the guy who talks about UFO and Elvis sightings.”

“Glad you could join us,” I said, “Now what’s running too hot for you today?”

“I read your book, and I’m planning to see your movie…,” he started.

“Oh, baby, the movie! Do you think Lithgow can do me justice on the big screen? I wanted Hanks, but, in the audition, he just didn’t seem all that passionate about heat sinks,” I said.

“Lithgow will be much stronger in the dance numbers, no doubt,” Herbie said, “But back to your book. You constantly harp on one thing: component junction temperature. You say the whole point of cooling electronics is to get the silicon chip temperature down.”

“Guilty,” I admitted, “It’s inside the components, where the heat is generated, that temperature-related failures occur. You can’t just measure exit air temperature and conclude your electronics are fine. You need to measure component temperature.”

Herbie continued, “As you say, We don’t sell air, we sell electronics. OK, so I’m following your philosophy, concentrating on component temperatures, keeping them inside their operating limits. But by keeping both of my eyes on junction temperature, I missed other thermal problems.”

“Sounds like you have a particular example in mind,” I said.

|

“I sure do,” he said, “My project is an electronic pet tracking system, sort of a combination of GPS, PCS and SPCA. You implant an ID chip under your dog’s skin, and if he runs away, the cops can home in on him to within 8 feet. I’m working on the box that does the tracking and map display, and it needs the highest speed processor they’ve got. When it’s tracking a really fast-moving dog, like a greyhound, that processor really hums, and kicks out 110 watts.”

“That processor is no dog,” I said, “So you want me to recommend a way of cooling it?”

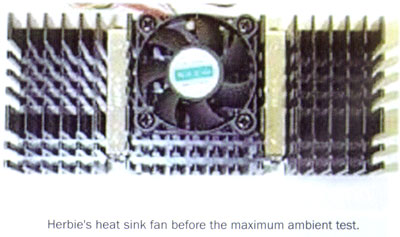

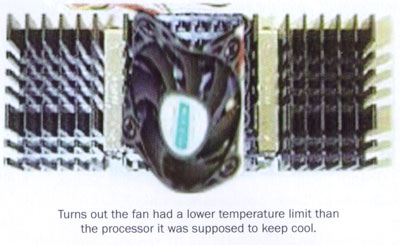

“No, that’s covered,” he answered, “I clamped on a big heat sink, with a fan right on top. In this case it was simple to know the processor junction temperature, because it has its own built-in temperature sensor, which you can display right on the computer screen.”

“How convenient. So what went wrong?” I asked.

“Everything looked good on paper,” Herbie said with a sigh, “Then we did the qualification test. If you’ve ever spent the night in jail or the dog pound, (and who hasn’t?) you know that they aren’t exactly the Ritz when it comes to climate control. That’s why according to the Law Enforcement and Animal Control Association Standard for Electronic Office and Counter-Violence Equipment, the room temperature can be as high as 40oC (104oF). In my bench test at normal room temperature of 20oC, the processor was 70oC, so I expected it to get up to 90oC during the maximum ambient test. That would have been OK, because its operating limit is 105oC. Then we put it in a test chamber at 40oC. Everything started out fine. The processor temperature went up to 88oC fairly quickly, and then stayed there. But after two hours, it suddenly went way up very quickly, and then the readings stopped because the processor failed.”

“That’s weird,” I said, “What happened? Was it a bad component? Did the heat sink fall off?”

“After we opened up the box, it was pretty obvious,” Herbie said, “The processor was 88oC, the heat sink was about 78oC, and the fan was about 75oC. I found out, unfortunately, after the test, that the inexpensive plastic fan I had chosen was rated to only 60oC. At 75oC the plastic fan body softened, and when it warped, the fan stopped turning. Without cooling air, the processor soon overheated and failed.”

|

“Ouch!” I said, “Sounds like you need a fan with a higher temperature rating.”

“Duh!” he retorted, “I know that now. But I was busy worrying about junction temperatures, not fan temperatures. I didn’t imagine a fan could overheat, until it was too late!”

The phone board was suddenly flooded (with three more) calls. Johnny started putting them on the air without asking me. He does that to bug me.

“Hi, this is Jane from Janesville. Herbie is right. You can’t just concentrate on the electronic component temperatures. Are you aware that for the European telecom industry, ETSI standards require that exhaust air from a cabinet cannot exceed 70oC, because it might blow into the cable plenum, where the electrical cable insulation is rated for only 70oC?”

I tried to answer, “Yeah, but . . .”

“Tony K., this is Gail from Galena. My DSP chip was OK with a case temperature of 90oC, but we routed optical fiber from a laser transceiver over it, and the plastic jacket on the fiber melted. It was only good up to 85oC. And melting wasn’t good, I found out.”

“Gail, of course you need to . . . ,” I tried.

“Am I on? OK, this is Joe from Springfield. Don’t forget about human contact temperature limits. That heat sink on the back of your power supply may keep your diodes happy at 100oC, but you sure don’t want somebody to touch it. Temperature can be a safety hazard, so keep touchable surfaces less than about 70o. Check your industry safety standards, like UL, for exact details. You don’t want people walking by your cabinet to get an accidental tattoo of your company logo if they brush against it. That kind of scar never looks good to a jury. Oh, and sorry, I couldn’t think up a clever radio pseudonym. I really am just Joe from Springfield.”

Herbie, still on the line, added, “And what about the printed circuit board? Doesn’t FR4 have some temperature limit? Maybe it’s OK for a wire-wound power resistor to be 175oC, but not if it toasts the board it’s soldered to. I think the boards I use have a Maximum Use Rating of only 105oC. You’ve steered us wrong, making us think only about junction temperature.”

“Yeah!” the other callers chimed in.

“OK,” I said, “I may have heavily emphasized junction temperature over the last few years. But I had to go overboard, at least a little, to compensate for the widespread myth that all you had to do was measure the exit air temperature and you were done.”

“Don’t whine, T-man, we still love you,” said Gail.

“That’s what this show is all about,” I said, settling back into my radio voice, “Love. Love and heat sinks.”

Johnny cranked his finger in the air, signaling me to wrap up before the news.

“Thanks, Herbie from Hereford, for your insightful call,”

I summed up, “We can always learn from our mistakes, but it’s easier to learn from someone else’s disasters, and your dog-finding machine meltdown is a classic. So here’s the lesson — we have to know the junction temperature of our components. That is a must. But we can’t forget about the rest of the things that the electronic system is made from: circuit board material, fans, electrical and optical cables, paper labels, and even sheet metal. They are all components, too, and they have temperature limits, just like op-amps, diodes and DRAMs. I wish I could give you a checklist of things to measure, but it wouldn’t have everything you might need to worry about on it. For example, how hot is a chip allowed to get if you implant it in a dog’s neck?”

“So until next week, this is Tony K. saying, keep cool. This segment was sponsored by Grandma Bonnie’s Boron Nitride particles. Put a little zip in your thermal grease with Grandma Bonnie’s.”

Tony Kordyban is the author of the book, Hot Air Rises and Heat Sinks: Everything You Know About Cooling Electronics Is Wrong (ASME Press), which for about ten minutes last year was outselling Gone with the Wind. He doesn’t really have a radio show, a movie deal, or a dog-tracking system, but maybe they are all good ideas.