Scientists have developed a new polymer-based thermal interface material (TIM) capable of conducing heat 20 times better than conventional polymer. Reliable in temperatures of up to 200°C, the modified material can be fabricated on heat sinks and heat spreaders and adheres well to components in servers, LEDs and mobile devices.

“Thermal management schemes can get more complicated as devices get smaller,” Baratunde Cola, an assistant professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology, said. “A material like this, which could also offer higher reliability, could be attractive for addressing thermal management issues. This material could ultimately allow us to design electronic systems in different ways.”

Amorphous polymer materials are poor thermal conductors, say the researchers, because the transfer of heat-conducing phonons is limited by the materials’ disordered state. Creating aligned crystalline structures in the polymers can improve heat transfer, but these structures can make the material brittle and susceptible to fracturing as devices continually expand and contract during heating and cooling cycles.

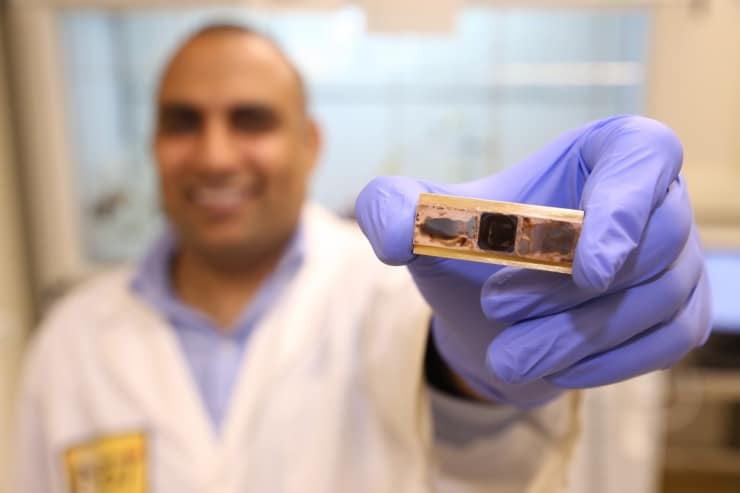

Developed by researchers from the Georgia Institute of Technology, University of Texas at Austin and the Raytheon Company, the new modified TIM is produced from polythiophene. Polythiophene is a conjugated polymer in which aligned polymer chains in nanofibers facilitate the transfer of phonons, but without the brittleness associated with crystalline structures, Cola said, adding that the formation of the nanofibers produces an amorphous material with thermal conductivity of up to 4.4 W/(m·K).

“Polymers aren’t typically thought of for these applications [referring to TIM use between chips and heat sinks] because they normally degrade at such a low temperature,” Cola said. “But these conjugated polymers are already used in solar cells and electronic devices, and can also work as thermal materials. We are taking advantage of the fact that they have a higher thermal stability because the bonding is stronger than in typical polymers.”

According to the researchers, the new polymer-based TIM has been tested up to 200°C, a temperature range suitable for various automotive applications. The material could also enable reliable thermal interfaces to be as thin as three microns—compared to TIMs with conventional materials measuring as much as 50 to 75 microns—making it ideal for use in microelectronics.

The technique still requires further research and development, but Cola believes it could be eventually scaled up for manufacturing and commercialization.

“There are some challenges with our solution, but the process is inherently scalable in a fashion similar to electroplating,” he said. “This material is well known for its other applications, but ours is a different use.”