Low-emissivity (Low-E) films are not new –they represent a mature technology in which a metal-oxide coated surface emits low levels of radiant thermal energy. Low-E films are widely used on window glasses in energy-efficient buildings. Low-E materials include metals like Aluminum foil which has a thermal emissivity /absorptance of 0.03 which means that it reflects 97 percent of radiant thermal energy. Their use in cooling of electronics components is still not as common as one would expect and for a good reason. Low-E materials must provide more than just high reflectance (which only helps alleviate irradiant heat flux); they must provide a mechanism to siphon off subsurface heat flux into the ambient by combined radiation and convection modes of heat transfer. Recently, researchers have discovered methods to accomplish just that –meta materials that succeed in maintaining the surface temperature lower than that of the ambient.

Infrared (IR) radiation occurs over a broad range of wavelengths from 6 to 30 microns. It is well known that passive cooling below ambient air temperature occurs at night by radiative cooling in which a device exposed to the sky radiates heat to outer space. How ever, during the day light hours, surfaces remain hotter with Solar irradiance and the ambient temperature governed largely by convection. This is due to the fact that molecules in the air can absorb heat at the higher and lower wavelengths of the IR spectrum. CO2 molecules typically absorb heat higher than O2 which leads to the green house effect.

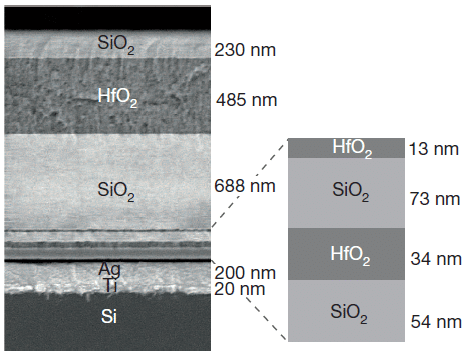

In 2014, researchers led by Prof. Shanhui Fan at Stanford University published their approach to radiative cooling during the daylight hours. Utilizing the transparency window in the atmosphere between wave lengths of 8 and 13microns, the Stanford team achieved a cooling of 5degC below the ambient air temperature under direct sunlight. To achieve daytime radiative cooling, the fabricated device has to meet a very stringent set of constraints as dictated by the overall power balance:

- First, it must reflect sunlight over visible and near-infrared wavelength ranges.

- Second, it must strongly emit thermal radiation while minimizing incident atmospheric thermal radiation by minimizing its emission at wavelengths where the atmosphere is opaque.

- Thus, the device must emit selectively and strongly only between 8 mm and 13 mm, where the atmosphere is transparent, and reflect at all other wavelengths.

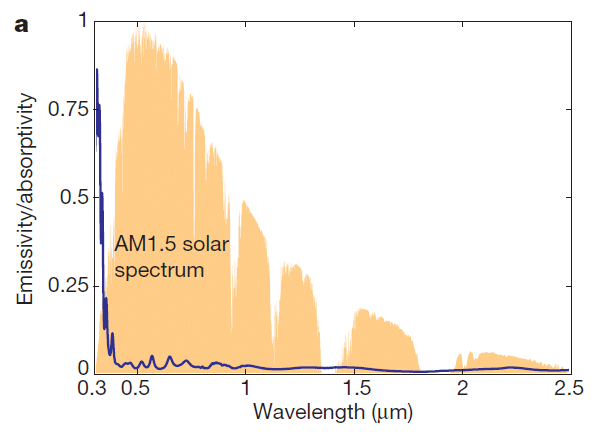

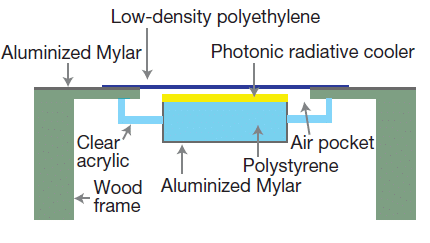

Figures 1a and 1b show some details of the apparatus used to test the radiative cooler developed at Stanford.

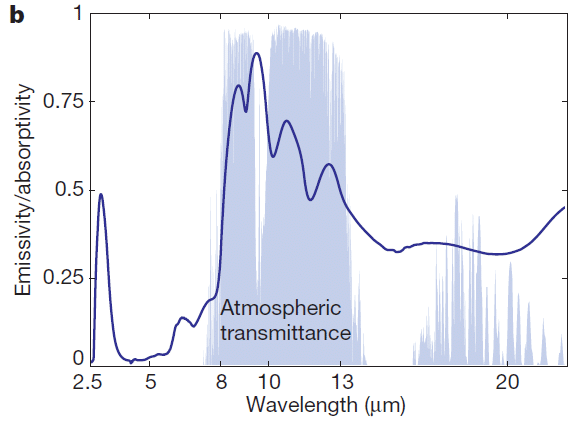

As shown in Figures 2a and 2b below, the response of Stanford device shows minimal absorption when integrated from 300nm to 4um where the solar spectrum is present, reflecting 97% of incident solar power at near-normal incidence. In Figure 2b, the device shows strong and remarkably selective emissivity in the atmospheric window between 8um and 13um. The research also reported that the photonic radiative cooler’s thermal emissivity persists to large angles, making it ideal for maximizing radiated power which is a hemispherically integrated quantity.

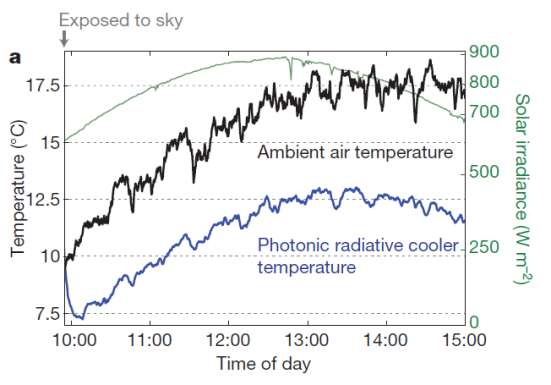

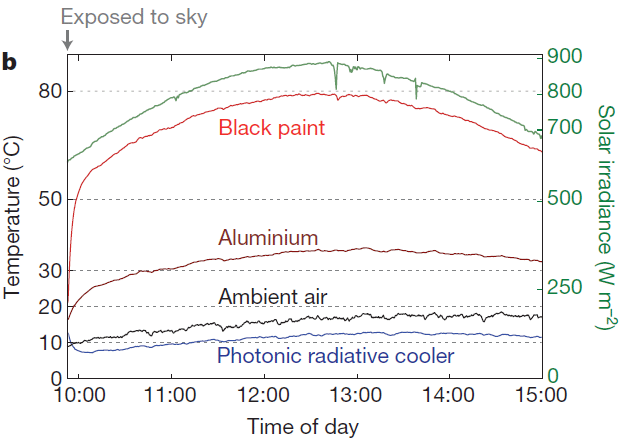

When exposed to direct sunlight exceeding 850W/m2 on a rooftop, the photonic radiative cooler cools to 4.9degC below the ambient air temperature and has a cooling power of 40.1W/m2 at ambient air temperature, as shown in Figures 3a & 3b.

Rooftop measurement of the photonic radiative cooler’s performance (blue) against ambient air temperature (black) on a clear winter day in Stanford, California. The photonic radiative cooler immediately drops below ambient once exposed to the sky, and achieves a steady-state temperature Ts of 4.9degC below ambient for over one hour where the solar irradiance incident on it (green) ranges from 800W/m2 to 870W/m2.

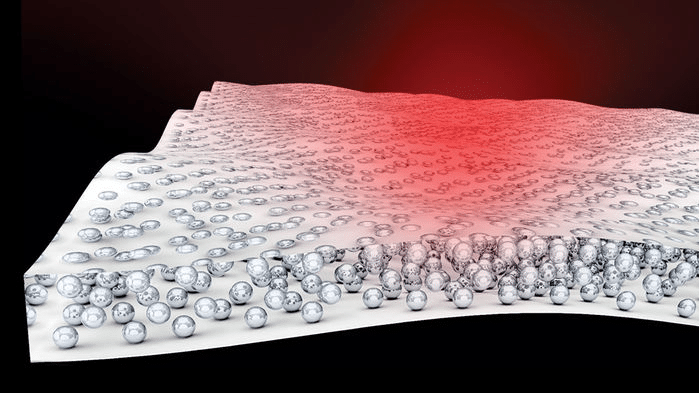

The Stanford research shows that the cold darkness of the Universe can be used as a renewable thermodynamic resource, even during the hottest hours of the day for cooling purposes including electronics cooling. How ever, this week things got even better for low cost cooling! A very recent summary reported by the Science Magazine based on the research from the University of Colorado, Boulder, shows a two-fold improvement in the cooling margin! Prof. Xiaobo Yin who studied the Stanford research in depth observed that the material worked in part by stimulating infrared photons to resonate between the layers of the film in a manner that made it a stronger IR emitter. Prof. Yin’s team found that a much simpler way to accomplish resonant IR behavior was to use glass beads of about 8um in diameter and deposited them on a sheet of Polymethylpentene. To achieve the high reflectance, the underside of plastic sheet was coated with Silver, as shown in the figure below.

In Prof. Yin’s experiments, the Silver-coated film absorbed only about 4% of incoming photons but concurrently siphoned off heat out of the surface it was bonded to and radiated that energy at a mid-IR frequency of 10 micrometers. In a manner identical to that observed in Stanford experiments, this caused the objects below to cool by as much as 10degC. Prof. Yin estimates that the new film can be made in a roll-to-roll setup for a cost of only $0.25 to $0.50 per square meter.

The foregoing point on roll-to-roll processing seems to be an excellent solution for advancing printed electronics and solar modules. One of the serious bottlenecks that limit the development of these products as well as thin flexible paper electronics is indeed thermal management. With the advances discussed in this blog, it now seems feasible to develop flexible and low cost printed electronics products that can enable new product innovations and opportunities. The cooling technology also has potential in consumer electronics applications.

You comments are welcome.