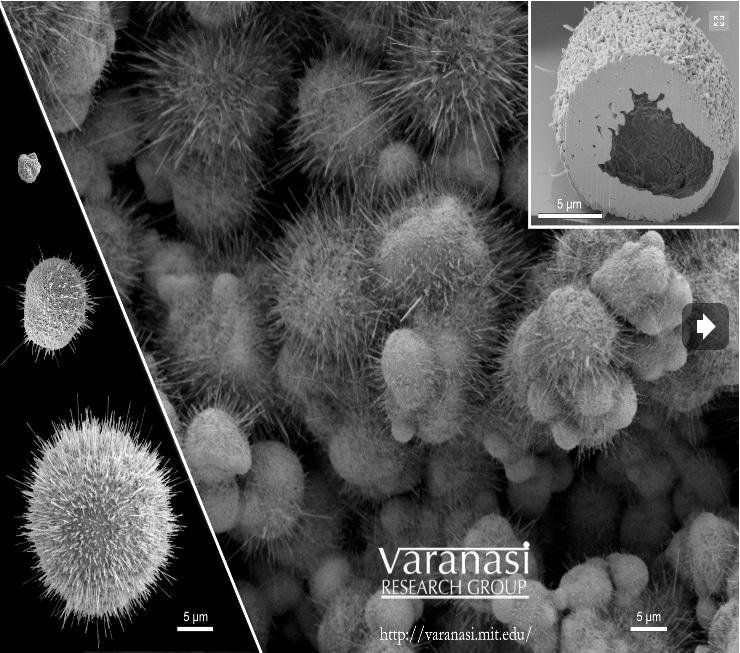

A well-known method of making heat sinks for electronic devices is a process called sintering, in which powdered metal is formed into a desired shape and then heated in a vacuum to bind the particles together. In a recent experiment, students at MIT led by Kripa Varanasi, d’Arbeloff Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering, tried sintering copper particles in air and instead of the expected solid metal shape, what they found was a mass of particles that had grown long whiskers of oxidized copper. The resulting process could turn out to be an important new method for manufacturing structures that span a range of sizes down to a few nanometers in size. These new structures could be used for managing the flow of heat in various applications ranging from power plants to the cooling of electronics.

Not only were the particles covered with fine wires, but the abundance of the wires turned out to be dependent on the size of the original copper particles. That means researchers can easily synthesize porous structures at various scales, in bulk, by selecting the particles they start out with: Particles smaller than a certain size sinter, while larger particles grow nanowires.